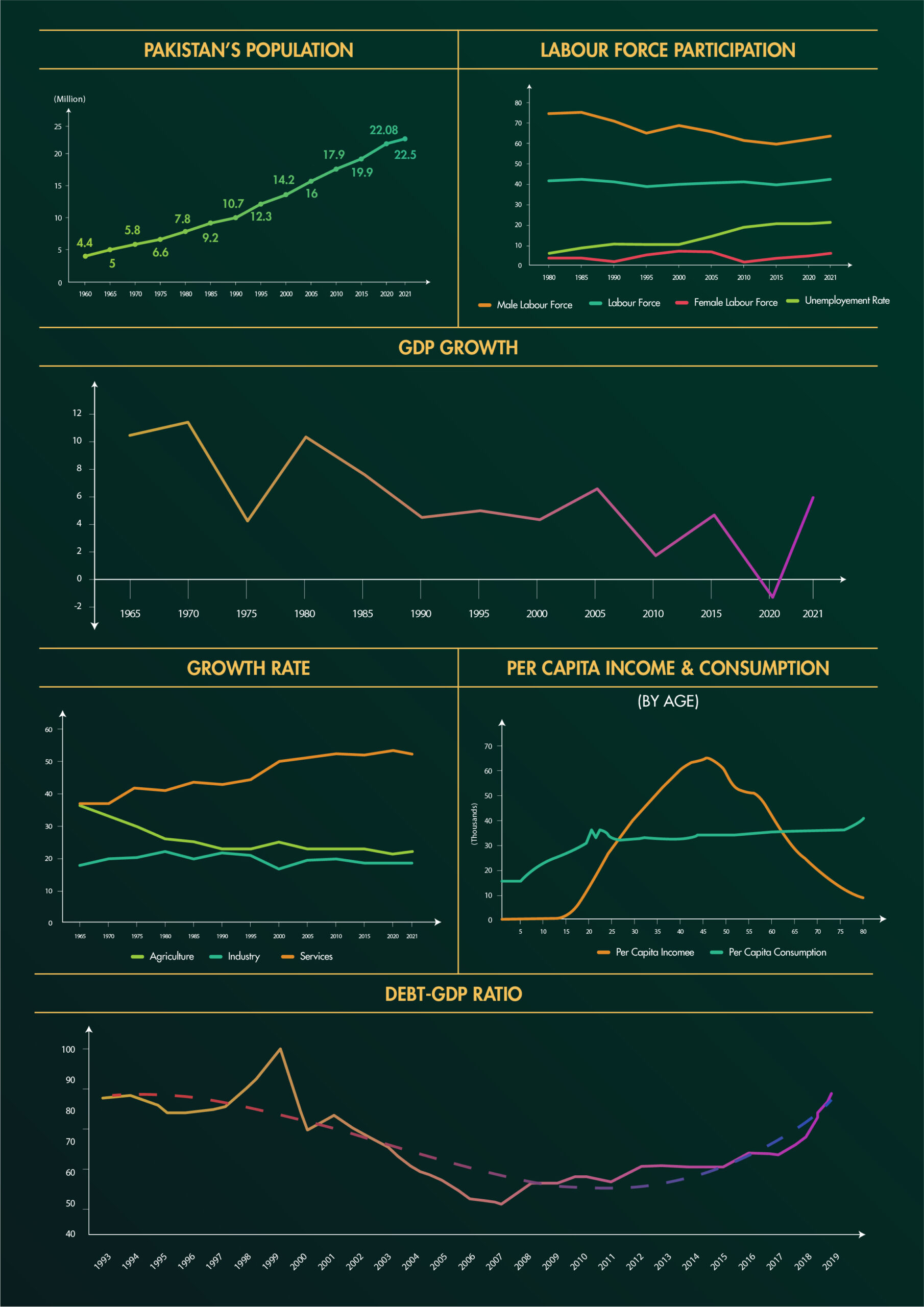

Pakistan’s aspiration to achieve upper-middle-income status by 2047, its centennial year, requires crucial decisions despite its turbulent history. While a 6% annual economic growth in the first four decades doubled per capita incomes and reduced poverty from 46% to 18% by the late 1980s, maintaining this trajectory amidst wars and political transitions was challenging. To secure a prosperous future, Pakistan must analyze past factors and embrace sustainable growth strategies. Despite the hurdles, similar transformations by other nations within 25 years offer inspiration. Understanding Pakistan’s socio-economic paradoxes over 75 years underscores the need for strategic planning and decisive actions to navigate towards sustained growth and development.

Phase I (1947-1958): Setting Foundations Amidst Challenges

Phase I (1947-1958): Setting Foundations Amidst Challenges

From 1947 to 1958, Pakistan’s socio-economic history saw the inception of its first five-year plan, mirroring the Russian model. The establishment of the State Bank of Pakistan aimed to jumpstart economic growth, accompanied by significant infrastructural expansions. The onset of the Korean War triggered a local economic boom through increased exports. However, by 1951, growth faltered due to funding shortages, exacerbated by monsoon floods causing production declines. Pakistan’s plea for economic aid from the United States and other allies marked the collapse of the five-year plan. Despite initial strides, financial constraints and natural disasters forced an early end to the program.

Phase II (1958-1971): Economic Resilience and Development

General Ayyub Khan assumed control in October 1958, overseeing Pakistan’s economic zenith. With international advisors, the Planning Commission initiated successful economic reforms. Despite the initial five-year plan’s failure, the second prioritized heavy industrial development, scientific advancement, and literature. GDP growth averaged 6%, doubling the previous decade’s rate. Manufacturing expanded by 9% annually, while agriculture grew by 4% with Green Revolution technology. Governance saw improvements, enhancing policy analysis and institution building.

Phase III (1971-1988): Trials and Transformations

Post-1971, a civil war led to East Pakistan’s separation, forming Bangladesh. This shattered Pakistan’s economy and its founding concept. The economic model once lauded internationally, faced domestic rejection. The fourth five-year plan was abandoned, and replaced by nationalization. Promises of distributive justice and Islamic socialism failed as nationalization hindered economic modernization. Pakistan fell behind East Asian countries, worsened by oil price shocks, droughts, and floods. Economic setbacks led to a reliance on external assistance.

Phase IV (1988-1999): Transition and Economic Challenges

The failure to comply with IMF agreements undermined Pakistan’s credibility in the international financial community. Local investors lost confidence when foreign currency deposits were frozen, while foreign investors were discontent with reopened power purchase agreements and legal action against a major foreign-owned power company. GDP growth decelerated to 4%, and agriculture output declined. The investment ratio dropped to 13.9% as foreign savings diminished, leading to significant domestic and external debt accumulation. Development expenditures plummeted, squeezing social sector spending and defence outlays. Unsustainable external debt levels doubled from $20 billion in 1990 to $43 billion in 1998. Exports stagnated, and Pakistan lost market share, while poverty and unemployment rates surged. Human development lagged, with the UN ranking Pakistan among the lowest development categories.

Phase V (2000s): Reforms, Challenges, and Democratization

The Planning Commission renamed five-year plans to Medium-Term Development Frameworks in 2004. MTDF 2005-2010 involved 32 working groups. Economic growth averaged 7%, up from 3.1% in 2001, reducing poverty by 5-10% and lowering unemployment from 8.4% to 6.5%. Primary school enrollment ratios rose, and foreign exchange reserves increased. The fiscal deficit remained around 4% of GDP, with investment at 23% of GDP, attracting $14 billion in foreign capital. Exchange rates remained stable. However, the government lacked reform vigour.

Phase VI (2010s): Political Instability and Economic Challenges

Pakistan faced hyperinflation, a budget deficit, and a debt crisis, inherited from the previous period. In 2013, the government sought IMF loans to address energy shortages, revenue collection, and balance of payments. By mid-decade, improved economic conditions followed as oil prices dropped, remittances and consumer spending rose, and foreign reserves reached $10 billion. The IMF program ended in 2016, though Pakistan struggled to meet reform criteria. Despite stable rupee-dollar rates until 2015, political instability persisted. From 2010 to 2020, three democratic regimes governed, but economic fluctuations persisted, with a 5.97% growth rate in 2021, spurred by industrial and agricultural growth. Political uncertainty, currency devaluation, and inflation plagued Pakistan, necessitating IMF loans and impacting economic performance.

Phase VII (2020-Present): Pandemic and Imperative Reforms

This period marks the pandemic’s impact and Pakistan’s structural reforms to stabilize the economy. COVID-19’s onset in 2020 sent shockwaves, prompting lockdowns and a significant economic slowdown. The service and manufacturing sectors suffered, but swift government fiscal and monetary policies helped stabilize the economy. Initiatives like the Ehsaas Emergency Cash Program provided relief to vulnerable populations. Despite challenges, Pakistan’s economy showed signs of recovery, with a 3.94% growth rate in fiscal year 2020-21. However, the pandemic highlighted the need for structural reforms, including revenue enhancement, energy sector efficiency, and addressing fiscal deficits. Pakistan’s heavy reliance on external financing underscores the urgency of a sustainable growth model reducing dependency on foreign loans.

The Path Forward: Navigating Challenges and Seizing Opportunities

For over 60 years, Pakistan has pursued project-based growth reliant on foreign aid, following the HAQ model of 1964. This approach emphasized infrastructure over capacity building and asset optimization, with 80% of projects focused on brick and mortar. However, true growth requires entrepreneurship, productivity, and innovation, not just physical capital. Despite reasonable progress, Pakistan lags in human, capital, and social development, posing significant challenges. Yet, Pakistan has historically overcome daunting obstacles, driven by shared values and dedicated leadership. Now, it needs a comprehensive approach to realize its vision: prioritizing human and social development, economic diversification, fiscal stability, public-private sector integration, investment, international cooperation, environmental sustainability, and public sector modernization. With proactive policies and effective implementation, Pakistan can transform its future over the next 25 years.

Leave a Reply